The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 to protect the voting rights of mostly black voters in mostly Southern states. It mandated, among other things, that jurisdictions covered by the law have new voting laws reviewed by the government to assure that they weren’t discriminatory.

That provision was tossed by the Supreme Court in 2013. A Texas voter ID law that had been rejected by the Department of Justice prior to the court’s decision was reintroduced immediately afterward — and was quickly found to be discriminatory.

During his confirmation hearing last year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions was asked about the Voting Rights Act.

“It is intrusive. The Supreme Court on more than one occasion has described it legally as an intrusive act, because you’re only focused on a certain number of states,” the then-Alabama senator said in January 2017.

It was a county in Alabama, Shelby County, that brought the lawsuit that led to the court’s decision. At the time Sessions celebrated the move: “There is racial discrimination in the country, but I don’t think in Shelby County, Alabama, anyone is being denied the right to vote because of the color of their skin,” he said. “It would be much more likely to have those things occur in Philadelphia, Chicago or Boston.”

That history is newly relevant because of the rationale offered by the Department of Justice in requesting that the Census Bureau add a question regarding citizenship to the 2020 survey. The Justice Department says the question is necessary because it requires specific data to identify violations of the Voting Rights Act.

“[H]aving these data at the census block level” — the most fine-grained unit at which the census gathers data — “will permit more effective enforcement of the Act,” wrote Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross in his letter to undersecretary Karen Dunn Kelley responding to Justice’s request. “Section 2 protects minority population voting rights.” Ross’s letter goes on to explain that the Census Bureau will honor Justice’s request and include a question about citizenship.

But the reason that the question is controversial is not Sessions’s background on the Voting Rights Act. It’s controversial because experts argue that the effect of the question will be to dampen participation in the census by those who immigrated to the country illegally.

The decennial census is intended to count the number of people living in the United States (regardless of immigration status or citizenship) and then to use that data to inform key decisions like government spending and allocation of House seats and electoral votes. If undocumented immigrants are less likely to respond to the census, the population figures in places that they live will be significantly lower than they might otherwise be.

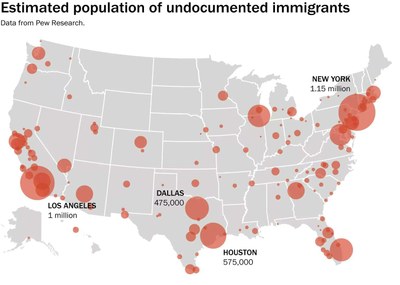

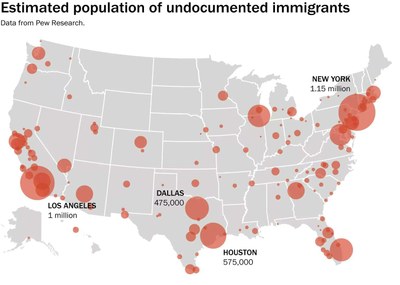

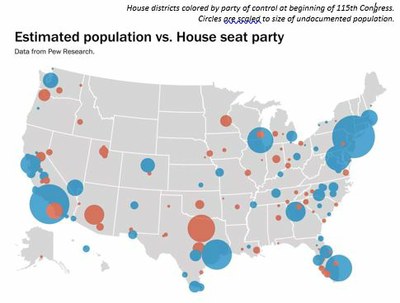

Pew Research estimated where those immigrants lived in a report released in February 2017. Of the 11 million or so immigrants living in the country without legal status, most live in cities.

It’s those cities that would see the most dramatic undercounts in the survey.

They already see undercounts. In the 2010 Census, the bureau estimated a 1.5 percent undercount of Hispanics and a 2.1 percent undercount among black Americans. The concern is that the first figure in particular would rise substantially if a citizenship question were added.

In his letter, Ross writes that he has seen little evidence that it would.

“[N]either the Census Bureau nor the concerned stakeholders could document that the response rate would in fact decline materially,” he writes. “In discussing the question with the national survey agency Nielsen, it stated that it had added questions from the [American Community Survey] on sensitive topics such as place of birth and immigration status to certain short survey forms without any appreciable decrease in response rates.”

A 2014 study seems to reinforce that idea, looking at response rates from surveys that include citizenship questions and finding that, for one survey, “the introduction of legal status questions does not appear to have an appreciable ‘chilling effect’ on the subsequent survey participation of unauthorized immigrant respondents.”

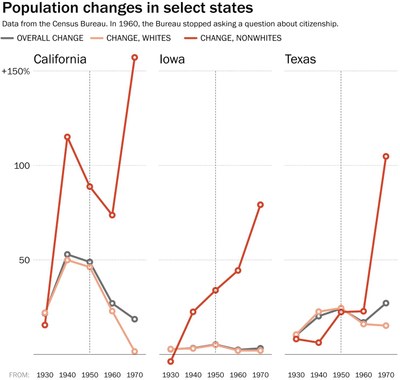

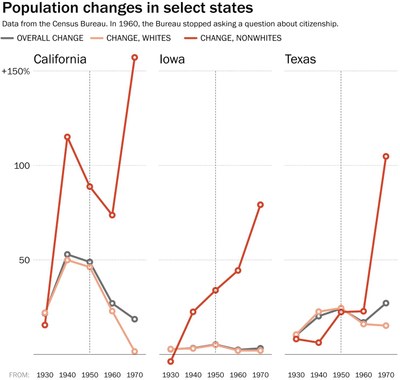

The Census Bureau asked about citizenship in all interviews in 1950. Between 1950 and 1960, the number of nonwhite residents identified in California, Iowa and Texas didn’t increase dramatically — but the varying definitions of racial and ethnic groups over that period make it tricky to assess any effect.

There are many other caveats worth mentioning.

The most significant is that the researchers in that 2014 study found a difference between privately operated surveys and government-run ones like the census. It compared two surveys, one private and one government-run, determining that “the rate of missing data between the two surveys appears to be consistent” with concerns expressed in a 2006 Government Accountability Office report determining that private-sector-operated surveys — like Nielsen’s — would see a better response. (Among other reasons, the GAO suggested that “[s]ome foreign-born persons are from countries with repressive regimes and thus have more fear of (less trust in) government than the typical U.S.-born person.”)

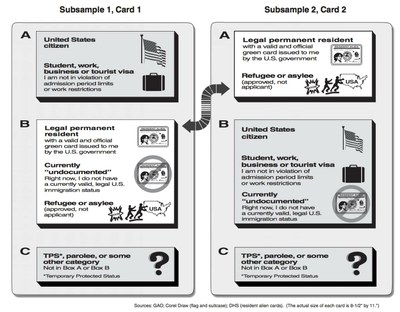

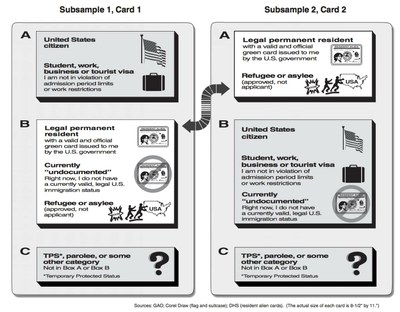

The GAO advocated using a system that offered respondents one of two cards and asked people to identify the group to which they belonged. By comparing responses from the two groups, the number of undocumented immigrants could be estimated.

The 2014 study also noted that it was using data from 2001 to 2004, “prior to the widespread emergence of immigrant enforcement measures at federal, state and local levels. It is therefore possible,” it concludes, “that the conclusions drawn here about the collection and use of survey data on legal status may not apply in the more recent enforcement context.”

That’s particularly pertinent now that the administration of President Trump has been unsparing in targeting those without legal immigration status. An average census block will include a few dozen people in a specific geographic area identified by bounding streets. Were undocumented immigrants to reply faithfully to the census question, it would be trivial for immigration officers to identify pockets of those who immigrated illegally.

That concern isn’t applicable only to undocumented residents. As Pennsylvania State University demographics professor Jennifer Van Hook wrote last month, focus groups conducted by the bureau last year showed that the concern was more widespread.

The Trump administration’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy may have increased mistrust among all immigrants, not just those who are undocumented. During focus group interviews conducted by the Census Bureau roughly six months into Trump’s presidency, immigrants appeared anxious and reluctant to cooperate with Census Bureau interviewers. They mentioned fears of deportation, the elimination of DACA, a “Muslim ban” and ICE raids. One respondent walked out when the questionnaire turned to the topic of citizenship, leaving the interviewer alone in his apartment.

Past census directors have repeatedly argued that adding such a question to the census would tamp down on responses, including in a brief filed with the Supreme Court.

“Nor is it possible to accurately obtain a count of voting age citizens by inquiring about citizenship status as part of the Census count,” four former bureau directors write in that document. “Recent experience demonstrates lowered participation in the Census and increased suspicion of government collection of information in general. Particular anxiety exists among non-citizens.”

Two other former directors joined that group to send a letter, obtained by The Washington Post, to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross in January making the same case.

In his letter, Ross admits that the bureau estimates that there would be an increase in the non-response follow-up (NRFU) total — the number of people that the bureau would need to contact directly after not receiving a response from the initial survey.

“The Bureau provided a rough estimate that postulated that up to 630,000 additional households may require NRFU operations if a citizenship question is added to the 2020 decennial census,” he wrote. This, though, was only a 0.5 percent increase, he said, and the bureau already anticipated that “NRFU operations might increase by 3 percent due to numerous factors, including a greater increase in citizen mistrust of government, difficulties in accessing the Internet to respond, and other factors.” (In their amicus brief with the Supreme Court, the four former bureau directors noted an increase in skepticism about government data-collecting prior to 2010.)

The average household in the United States was about 2.5 people in 2017. Ross’s estimate of additional non-responses, then, means about 1.5 million fewer people tallied in the bureau’s first pass as a result of the new question.

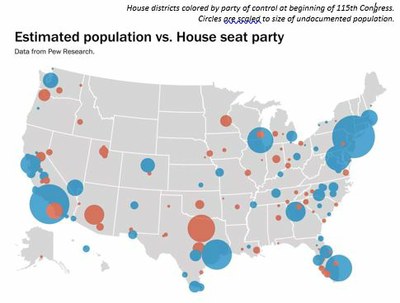

It’s impossible not to note that the effects of undercounting these residents will fall heavily in more Democratic states and cities. Pew’s analysis of where the undocumented population lives finds, unsurprisingly, that they mostly live in Democratic areas (in part because they mostly live in cities).

Those areas would see fewer resources allocated by the government and smaller population estimates for House redistricting should the citizenship question be added and response rates decline.

Again, the rationale provided by Sessions’s Justice Department is that it is concerned about identifying violations of the Voting Rights Act. If the net effect is to potentially significantly undercount the number of immigrants living in the country illegally, that’s a risk that the administration seems to be willing to take.

Article posted from The Washington Post

The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 to protect the voting rights of mostly black voters in mostly Southern states. It mandated, among other things, that jurisdictions covered by the law have new voting laws reviewed by the government to assure that they weren’t discriminatory.

That provision was tossed by the Supreme Court in 2013. A Texas voter ID law that had been rejected by the Department of Justice prior to the court’s decision was reintroduced immediately afterward — and was quickly found to be discriminatory.

During his confirmation hearing last year, Attorney General Jeff Sessions was asked about the Voting Rights Act.

“It is intrusive. The Supreme Court on more than one occasion has described it legally as an intrusive act, because you’re only focused on a certain number of states,” the then-Alabama senator said in January 2017.

It was a county in Alabama, Shelby County, that brought the lawsuit that led to the court’s decision. At the time Sessions celebrated the move: “There is racial discrimination in the country, but I don’t think in Shelby County, Alabama, anyone is being denied the right to vote because of the color of their skin,” he said. “It would be much more likely to have those things occur in Philadelphia, Chicago or Boston.”

That history is newly relevant because of the rationale offered by the Department of Justice in requesting that the Census Bureau add a question regarding citizenship to the 2020 survey. The Justice Department says the question is necessary because it requires specific data to identify violations of the Voting Rights Act.

“[H]aving these data at the census block level” — the most fine-grained unit at which the census gathers data — “will permit more effective enforcement of the Act,” wrote Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross in his letter to undersecretary Karen Dunn Kelley responding to Justice’s request. “Section 2 protects minority population voting rights.” Ross’s letter goes on to explain that the Census Bureau will honor Justice’s request and include a question about citizenship.

But the reason that the question is controversial is not Sessions’s background on the Voting Rights Act. It’s controversial because experts argue that the effect of the question will be to dampen participation in the census by those who immigrated to the country illegally.

The decennial census is intended to count the number of people living in the United States (regardless of immigration status or citizenship) and then to use that data to inform key decisions like government spending and allocation of House seats and electoral votes. If undocumented immigrants are less likely to respond to the census, the population figures in places that they live will be significantly lower than they might otherwise be.

Pew Research estimated where those immigrants lived in a report released in February 2017. Of the 11 million or so immigrants living in the country without legal status, most live in cities.

It’s those cities that would see the most dramatic undercounts in the survey.

They already see undercounts. In the 2010 Census, the bureau estimated a 1.5 percent undercount of Hispanics and a 2.1 percent undercount among black Americans. The concern is that the first figure in particular would rise substantially if a citizenship question were added.

In his letter, Ross writes that he has seen little evidence that it would.

“[N]either the Census Bureau nor the concerned stakeholders could document that the response rate would in fact decline materially,” he writes. “In discussing the question with the national survey agency Nielsen, it stated that it had added questions from the [American Community Survey] on sensitive topics such as place of birth and immigration status to certain short survey forms without any appreciable decrease in response rates.”

A 2014 study seems to reinforce that idea, looking at response rates from surveys that include citizenship questions and finding that, for one survey, “the introduction of legal status questions does not appear to have an appreciable ‘chilling effect’ on the subsequent survey participation of unauthorized immigrant respondents.”

The Census Bureau asked about citizenship in all interviews in 1950. Between 1950 and 1960, the number of nonwhite residents identified in California, Iowa and Texas didn’t increase dramatically — but the varying definitions of racial and ethnic groups over that period make it tricky to assess any effect.

There are many other caveats worth mentioning.

The most significant is that the researchers in that 2014 study found a difference between privately operated surveys and government-run ones like the census. It compared two surveys, one private and one government-run, determining that “the rate of missing data between the two surveys appears to be consistent” with concerns expressed in a 2006 Government Accountability Office report determining that private-sector-operated surveys — like Nielsen’s — would see a better response. (Among other reasons, the GAO suggested that “[s]ome foreign-born persons are from countries with repressive regimes and thus have more fear of (less trust in) government than the typical U.S.-born person.”)

The GAO advocated using a system that offered respondents one of two cards and asked people to identify the group to which they belonged. By comparing responses from the two groups, the number of undocumented immigrants could be estimated.

The 2014 study also noted that it was using data from 2001 to 2004, “prior to the widespread emergence of immigrant enforcement measures at federal, state and local levels. It is therefore possible,” it concludes, “that the conclusions drawn here about the collection and use of survey data on legal status may not apply in the more recent enforcement context.”

That’s particularly pertinent now that the administration of President Trump has been unsparing in targeting those without legal immigration status. An average census block will include a few dozen people in a specific geographic area identified by bounding streets. Were undocumented immigrants to reply faithfully to the census question, it would be trivial for immigration officers to identify pockets of those who immigrated illegally.

That concern isn’t applicable only to undocumented residents. As Pennsylvania State University demographics professor Jennifer Van Hook wrote last month, focus groups conducted by the bureau last year showed that the concern was more widespread.

The Trump administration’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy may have increased mistrust among all immigrants, not just those who are undocumented. During focus group interviews conducted by the Census Bureau roughly six months into Trump’s presidency, immigrants appeared anxious and reluctant to cooperate with Census Bureau interviewers. They mentioned fears of deportation, the elimination of DACA, a “Muslim ban” and ICE raids. One respondent walked out when the questionnaire turned to the topic of citizenship, leaving the interviewer alone in his apartment.

Past census directors have repeatedly argued that adding such a question to the census would tamp down on responses, including in a brief filed with the Supreme Court.

“Nor is it possible to accurately obtain a count of voting age citizens by inquiring about citizenship status as part of the Census count,” four former bureau directors write in that document. “Recent experience demonstrates lowered participation in the Census and increased suspicion of government collection of information in general. Particular anxiety exists among non-citizens.”

Two other former directors joined that group to send a letter, obtained by The Washington Post, to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross in January making the same case.

In his letter, Ross admits that the bureau estimates that there would be an increase in the non-response follow-up (NRFU) total — the number of people that the bureau would need to contact directly after not receiving a response from the initial survey.

“The Bureau provided a rough estimate that postulated that up to 630,000 additional households may require NRFU operations if a citizenship question is added to the 2020 decennial census,” he wrote. This, though, was only a 0.5 percent increase, he said, and the bureau already anticipated that “NRFU operations might increase by 3 percent due to numerous factors, including a greater increase in citizen mistrust of government, difficulties in accessing the Internet to respond, and other factors.” (In their amicus brief with the Supreme Court, the four former bureau directors noted an increase in skepticism about government data-collecting prior to 2010.)

The average household in the United States was about 2.5 people in 2017. Ross’s estimate of additional non-responses, then, means about 1.5 million fewer people tallied in the bureau’s first pass as a result of the new question.

It’s impossible not to note that the effects of undercounting these residents will fall heavily in more Democratic states and cities. Pew’s analysis of where the undocumented population lives finds, unsurprisingly, that they mostly live in Democratic areas (in part because they mostly live in cities).

Those areas would see fewer resources allocated by the government and smaller population estimates for House redistricting should the citizenship question be added and response rates decline.

Again, the rationale provided by Sessions’s Justice Department is that it is concerned about identifying violations of the Voting Rights Act. If the net effect is to potentially significantly undercount the number of immigrants living in the country illegally, that’s a risk that the administration seems to be willing to take.

Article posted from The Washington Post